Barrister, Parliamentarian, and Judge, Charles Arthur Russell is little remembered today, even by lawyers. But in his own time he was a towering national figure, who astonished his contemporaries, both within and without the legal professions, with the raw emotive force of his advocacy. Few legal personalities of the late 19th and early 20th Century had sufficient claim to fame to merit being captured in oils by celebrity portraitist John Singer Sargent, but Sargent produced two paintings of Russell. And when Russell died unexpectedly in 1900, the newspapers were filled for days with tributes, summations of his career, and the reminiscences of people who had known and worked with him.

The second Commercial Judge was, like the first, an Irish Catholic. As Lord Chief Justice and head of Queen's Bench Division, Russell had many demands on his time, which left him relatively few opportunities to sit in the Commercial Court. As a result, he made little impression as a Commercial Judge. But as a vigorous and reforming Chief Justice who energetically supported the creation of a Commercial Court where his predecessor had implacably opposed it, Russell was one of the most important judicial figures in the Court's history.

Russell was born in Newry in 1832. He went to school in Newry, Belfast, and Dublin, but was not academically distinguished. (He later entered Trinity College, Dublin, but abandoned his degree when he left Ireland for a career at the English Bar.) Russell began his legal career in Newry in 1849, as an articled clerk to a local solicitor. He qualified as a solicitor in 1854, and worked in Belfast, Londonderry, and the local courts of Counties Down and Antrim. Solicitors had rights of audience in the magistrates' courts, and it was while defending clients before the magistrates that Russell first demonstrated that he had a natural talent for advocacy. In 1856, he moved to London to become a barrister, and joined Lincoln's Inn. Roman Catholics of Russell's era were not subject to the legal discriminations which had effectively excluded earlier generations from the professions, but it was still a brave move, and one which showed the ambition and determination which were to characterise Russell's career.

One of John Singer Sargent’s two 1899 portraits of Lord Russell. This is in Lincoln’s Inn. The other (or rather a replica, by the artist himself) is in the National Portrait Gallery.

Russell started out as a pupil in Chancery chambers, but the technicalities of land law and conveyancing did not fire his enthusiasm, and he soon moved across to common law work. He was called to the Bar in 1859. Joining the Northern Circuit, he made Liverpool the focus of his early practice. He was an almost instant success. Liverpool generated a significant quantity of shipping, marine insurance, and sale of goods work, and much of it was tried locally, particularly in the Court of Passage, a city court with ancient origins and with a jurisdiction somewhere between the county courts and the High Court in London. Russell became an established Passage practitioner. He also wrote a book about the Court’s practice and procedure, and even applied to become a Passage Judge when a vacancy arose in the mid 1870’s, though without success. But Russell did not confine himself to commercial litigation, and developed a relatively broad common law practice. As Russell’s reputation grew, he based himself increasingly in London. His appointment as Queen's Counsel in 1872, after barely a dozen years in practice, is evidence of his ability and success.

As a QC, Russell appeared in cases involving subject-matter from libel to wills, railways to elections, and local government to divorce. But shipping, marine insurance, and sale of goods litigation remained a mainstay of his practice. His first reported case as leading counsel was Liver Alkali v Johnson (1871-72) LR 7 Ex 267 and (1873-74) LR 9 Ex 338, an important authority on the obligations of common carriers. And in 1887, he appeared in a trilogy of significant cases in the House of Lords which analysed the meaning of the notoriously elusive phrase “perils of the sea”: The ‘Inchmaree’ (1887) 12 App Cas 484 and Hamilton v Pandorf (1887) 12 App Cas 518, in which the issues went to the scope of cover when the phrase was used in a marine insurance policy; and The ‘Xantho’ (1887) 12 App Cas 503, where the question was the degree of protection afforded to a shipowner by a “perils of the sea” exemption in a bill of lading. The trio of decisions established that the phrase must be given a uniform meaning whatever the contractual context, although the Lords’ attempts to explain the precise content and limits of that meaning left much room for argument in future cases. The “perils of the sea” decisions were among more than thirty cases which Russell argued in the House of Lords. Prominent among the others were Mogul Steamship v McGregor [1892] 2 AC 25, in which Russell persuaded the Lords that his clients, a cartel of shipowners, committed no actionable wrong by combining to undercut the rates of the plaintiff, an owner who was not a member of the cartel. As a QC in commercial cases, Russell worked with future Commercial Judges George Phillimore, John Bigham, and Joseph Walton, as well as other leading commercial juniors such as John Gorell Barnes and Arthur Cohen.

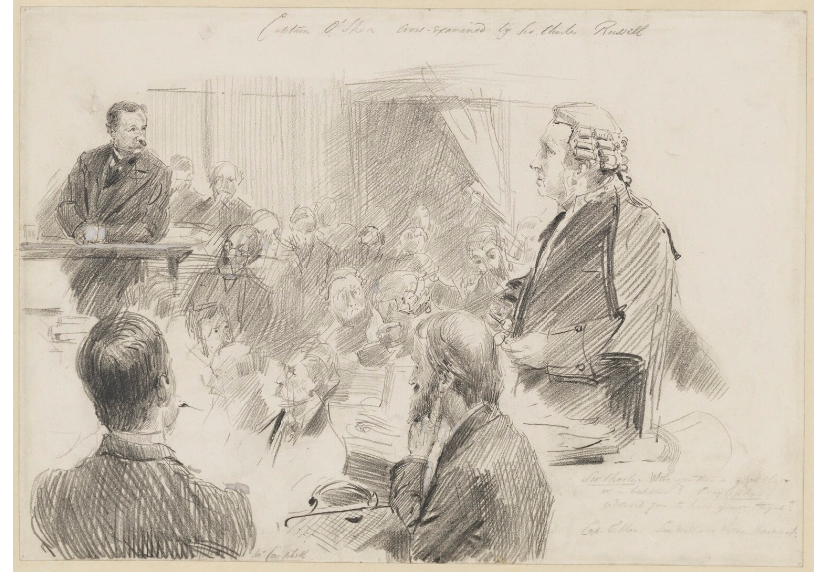

The Parnell Commission was one of the most prominent cases of Russell’s career at the Bar.

Russell achieved his greatest public prominence at the Bar in cases far removed from shipping and international trade. He represented Charles Stewart Parnell MP at hearings of the Commission which was established in 1888 to investigate allegations that Parnell and others prominent members of the Irish Home Rule movement were complicit in murder and disorder. Under Russell's searching cross-examination, the key evidence proved to be fraudulent. Russell also appeared in the criminal Courts. Most famously, he defended Florence Maybrick (with future Commercial Judge and Master of the Rolls William Pickford as his junior) in a sensational poisoning case. Rather against Russell's better judgment, his client insisted on taking the course which was then open to criminal defendants (though now long abolished) of making a statement from the dock without submitting to cross-examination. Her performance did not make a favourable impression, and was probably a major factor in the jury decision to convict her of doing her husband to death with arsenic, a verdict which was widely seen as a miscarriage of justice. The mandatory death sentence was commuted to a term of imprisonment, but Russell worried about the case for the rest of his days.

Russell was regarded as one of the most compelling advocates of his time. It was said that the power of his advocacy lay not so much in flights of eloquence as in the vehemence and conviction with which he expressed himself, which created an aura of moral authority. But this approach had its downsides. Russell was often too ready to identify with his client's cause, and correspondingly to regard anyone who did not share his viewpoint as aligning themselves with the forces of injustice. This tendency to view his cases in black and white moral terms, combined with a naturally short temper, made him aggressive in cross-examination and frequently personally offensive to opposing counsel. Even J.C. Mathew, who was a good friend and much admired Russell's forensic skills, conceded that he could be an unpleasant antagonist. He was generally rather less obnoxious in those commercial cases in which the evidence turned more on the meaning of documents than on examination of witnesses.

Russell’s forceful courtroom presence, sketched by Sydney Prior Hall (1842-1922) in 1889.

Russell was much interested in politics, and particularly in Irish affairs. When he moved to London, he started writing a weekly column on current affairs for a Dublin newspaper. He was elected MP for Dundalk in 1880, as an independent Liberal, but appears quite quickly to have aligned himself with the mainstream Liberal party. His speeches in the Commons mostly focussed on Irish matters. He advocated Irish Home Rule, and when the Liberals split in the mid-1880's over Gladstone's support for this policy, Russell naturally sided with the Gladstonian majority. Moving to an English constituency (and declining the offer of a place on the Bench in 1882), he was Attorney-General for six months during Gladstone's short-lived third ministry, then for eighteen months after Gladstone became Prime Minister for the final time in 1892. During this second period in office, Russell represented Great Britain in the Bering Sea Arbitration, the second major modern arbitration between nation states, which was convened to settle a dispute with the United States about sealing rights in the Arctic. The Award went Britain's way. In accordance with the custom of the times, Russell also maintained a private practice alongside his government work while Attorney-General: indeed, his last year at the Bar was his most lucrative, since his high-profile status as the senior government Law Officer enabled him to raise his fees for private work.

In April 1894, the hugely-admired and much-liked Charles Bowen died, less than a year after his appointment as a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary. Russell was appointed as his successor, styling himself Baron Russell of Killowen after a small village on Carlingford Lough, not far from his native Newry. Since Russell had shown little evidence of being a profound jurist suited to decide the most important cases in the highest court of appeal, the appointment can only be understood as political. But this was far from unique at the time: Russell's fellow Lords of Appeal MacNaghten and Watson owed their positions to political connections.

Russell’s tenure as a Law Lord was even briefer than Bowen's, and extended to only four reported cases (concerned with tax, wills, joinder of parties, and the registration of patent attorneys in Ireland, though he later sat in a bill of lading case in the Lords during his time as Chief Justice). In June 1894, the long-serving but almost entirely ineffectual Lord Chief Justice and President of the Queen's Bench Division, Lord Coleridge, died. By established convention, the Attorney-General of the day was entitled to claim the Chief Justiceship if it fell vacant, and although Russell had in fact (just) ceased to be Attorney-General, he got the job. He was the first Roman Catholic Lord Chief Justice since Stuart times.

News of the appointment received a mixed reception. The legal press welcomed it, on the grounds that Russell's dynamism was just what the Queen's Bench needed after years of lethargic leadership. On the other hand, Russell's established reputation for obnoxiousness was far from inspiring for legal practitioners faced with the prospect of appearing in his Court. In the event, Russell proved to be a generally restrained Judge, while expectations that he would reinvigorate the Queen's Bench proved justified. In particular, he was instrumental in the creation of the Commercial Court.

With a significant commercial practice of his own, Russell was fully alive to the decline of commercial litigation in the Queen's Bench during the 1880's and 1890's, the result, it was widely accepted, of excessive delay and cost, themselves caused by inefficient practices and procedures. The idea of some form of specialist Court as a response to these problems had been gaining support since the late 1880's. Lord Coleridge had vetoed the proposal, partly because he was in essence opposed to reform of any kind, partly because a specialist Court with specialist Judges implied that some Judges were not fit to try commercial cases. It was perfectly obvious that this was indeed the case. But, to Coleridge's mind, the principle that all Judges were equal must be maintained, whatever the facts. Russell, on the other hand, supported a Commercial Court. Soon after taking office, he asked the Rules Committee to draft amendments to the Rules of the Supreme Court to establish one. The Committee tied themselves up in knots over how to define a commercial case, and eventually declared that the task was impossible.

Undeterred, Russell decided that not only was it not necessary to have a definition, but it was not necessary to change the Rules either. Whether or not T.E. Scrutton was right that Russell was largely responsible for the drafting of the Notice as to Commercial Causes, he was the driving force which pushed the initiative through in the face of residual judicial opposition, the obstructiveness of the Rules Committee, and the pessimism of doubters who said that even a change to the Rules was not enough, and that effective reform required an Act of Parliament. At a meeting of the Queen's Bench Judges summoned by Russell in early 1895, the Notice as to Commercial Causes was endorsed, and Russell’s fellow Irishman and friend J.C. Mathew J was chosen as the first Commercial Judge. Russell himself was named as the principal substitute to deal with commercial cases when Mathew was not available.

An elaborate system of rules for the Commercial Court was set up. It was largely the work of that very great lawyer - even a greater lawyer than he was an advocate - Lord Russell of Killowen. T.E. Scrutton (1923) 1 Cambridge Law Journal, p.16. Scrutton’s fanciful description of the Notice as to Commercial Causes as “elaborate” rather casts doubt upon the reliability of his account.

Russell acted as Commercial Judge in July 1895, while Mathew was on Circuit, and again in March 1896. But there were many demands on the time of the Lord Chief Justice, and his reported Commercial Court decisions are confined to about a dozen cases of no very great significance, although Caffin v Aldridge [1895] 2 QB 366 is still cited by textbooks on the scope of a “liberty to call at any ports” under a contract of carriage. Russell's immense importance in the history of the Commercial Court is as a determined and energetic reformer, not as a Judge.

In the summer of 1900, Russell fell seriously ill while on Circuit at Chester, afflicted by what the newspapers described vaguely as "gastritis". He returned to London to rest and recuperate. But his condition did not improve, and his doctors decided on 9th August that an emergeny operation was essential. The surgery seemed to go well, with the patient apparently beginning to regain strength. But Russell's condition deteriorated rapidly in the early hours of the following morning, and he died, in his home, with members of his family around him. The family was a large one. Russell had married Ellen Mulholland, daughter of a Belfast doctor, in 1858. The formidable Ellen bore five sons and four daughters, all of whom survived their father. The second and and fourth sons, Charles and Francis, followed their father into the law: Charles founded a solicitors’ firm which still bears his name, while Frank went to the Bar and became a Chancery Judge in 1918 and a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary in 1928. Frank's own son, Charles Ritchie, became a Chancery Judge in 1960 and a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary in 1975. Frank and Charles Ritchie both styled themselves Baron Russell of Killowen, after Charles Arthur, the first Baron. This appointment of a father, son, and grandson was unique in the history of the judicial House of Lords.

Russell was not an enormously cultured individual. His main hobbies were games of chance (he was addicted to whist and picquet) and horseracing (he bought a country house near Epsom racecourse). Although his public persona was generally forbidding, and there is little evidence that he had a developed sense of humour, he was fond of socializing and had a circle of loyal friends, who must have seen a lighter side of his nature.

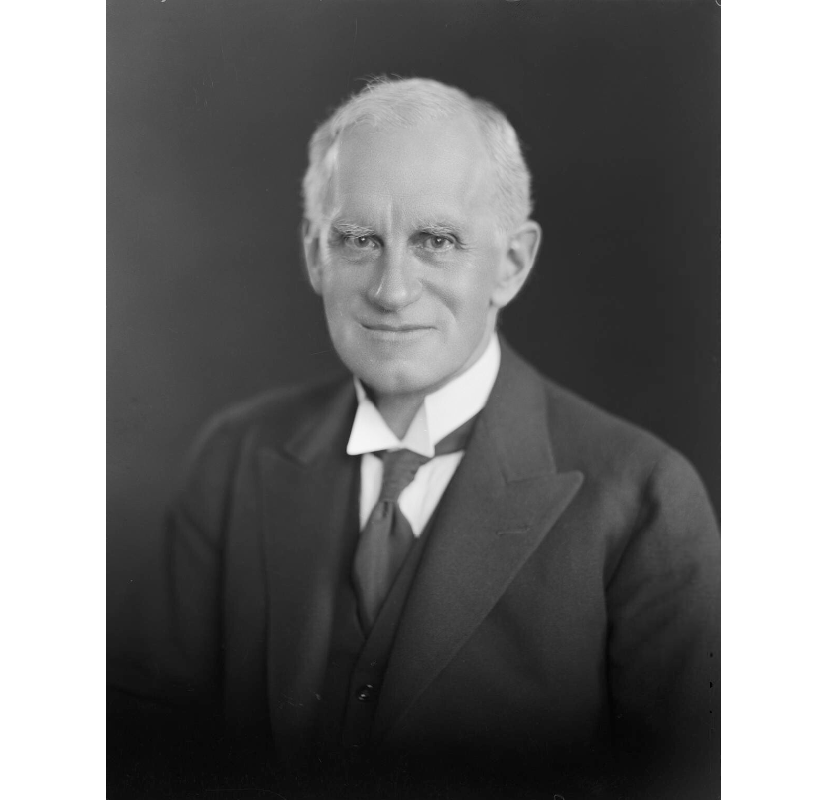

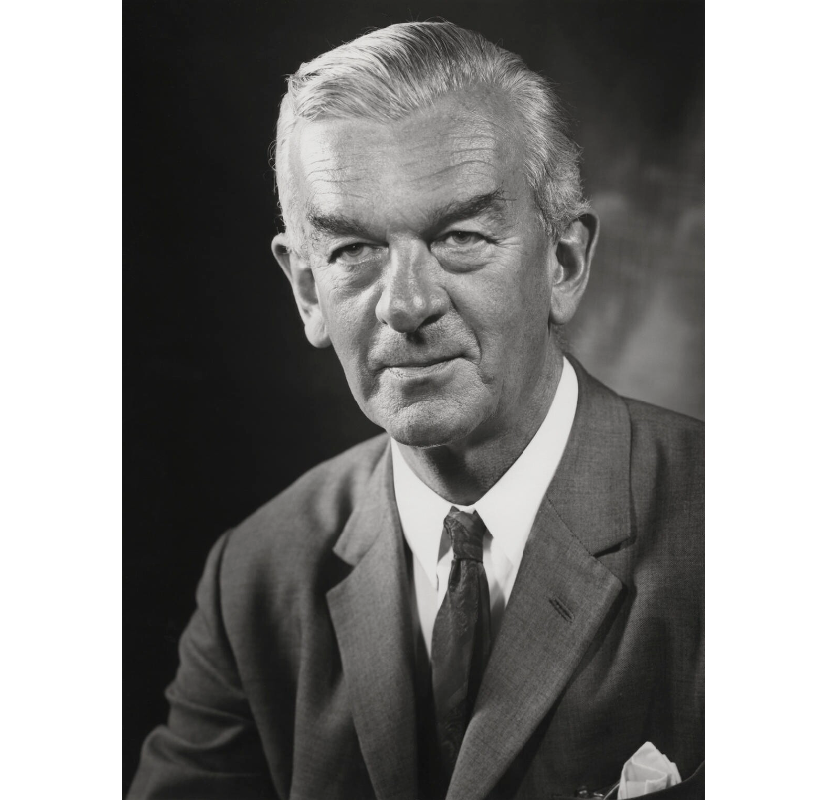

Three generations of Lords Russell of Killowen in the National Portrait Gallery: (from left) Charles Arthur, Francis Xavier, and Charles Ritchie.